What We Talk About When We Talk About Carver

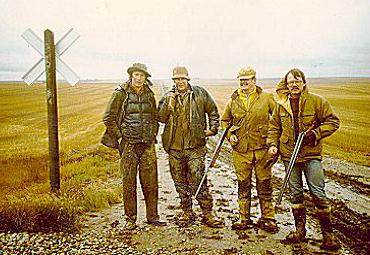

Richard Ford, Raymond Carver, David Carpenter, Bill Robertson

Richard Ford, Raymond Carver, David Carpenter, Bill RobertsonPhoto by Peter Nash

What We Talk About When We Talk About Carver

THURSDAY,

SEPTEMBER 23, 1986

"Gettin kinda dark out," says Robertson.

Honor leans toward me. "Bill

says it's -"

"I heard."

"Oi," she says.

"How do we know these guys

can shoot?" says Calder. "Maybe they're as rusty as we are."

"They can shoot."

"Hey, Carp, isn't it gettin

kinda dark out?" Robertson asks again.

I mumble something and weave

through the traffic on 11th Street, eyeing the dark gray horizon,

then accelerate for an orange light. Honor clutches the dash.

"Watch

out," she says.

"It's okay."

In September, in Saskatoon,

the evening light seems to vanish like a memory of August. Every

fall this happens and every fall I get ambushed by the rapid change.

You start thinking about winter for weeks before the Grey Cup or

the World Series. It's unsettling. It makes me brood on the brevity

of life.

"What if someone hears our

shots in the dark?" Robertson asks. He can't quite believe what's

going on. "What if they call the cops?"

"There's still some light,"

I counter.

"Where?" Calder asks.

Honor starts to laugh. The

other two join in.

Raymond Carver is coming to

Saskatoon. He will arrive tomorrow with his friend Richard Ford.

They are bringing their shotguns and expect to hunt with ... well

... hunters. I am determined that all of my hunters will make a

good showing. They will act like Saskatchewanians. Bob Calder (a

biographer) will re-discover that feeling of squinting down the

barrel of a twelve gauge, and Bill Robertson (a poet) will cease

to wonder how to work his safety catch. He's just bought his first

shotgun, an old twelve gauge double, for twenty dollars. Calder

last hunted in 1963. I am the veteran here. I last fired a shotgun

four years ago.

"Seriously though," says Calder.

"It is pretty dark out."

"Maybe we can use the headlights,"

I offer. My determination is still strong, but my voice sounds limp.

My determination is strong

because in 1982 I stumbled on Carver's stories and felt I just had

to meet this guy. Bring him up here for a reading. The question

was, how? Our English Department is strapped for visiting speaker

funds. Then I read "Distance," one of Carver's stories in Fires, and I began to see a way. In this

story a young man is about to go goose-hunting when his baby breaks

out in a crying spell. His young wife suspects the baby is seriously

ill, but neither parent knows for sure. She prevails upon her husband

to stay home and he misses out on his hunt. The baby stops crying

and soon recovers. This story comes to us twenty years later when

the marriage is long over.

An idea began to grow. I would

invite Carver to read on campus (where I teach on alternate years).

Art Sweet, a writer friend of mine, somehow dug up the address of

Carver's agent. I wrote to Carver. Let the critics say what they

will about "Distance" (... a poignant examination of lost bliss

... a portrait of the raconteur as exile in time and space ...),

its ultimate meaning is a far more fundamental cry from the heart:

Will somebody please take me goosehunting?

On January 19, 1986 Raymond

Carver answered my letter and said yes, we might be able to work

something out.

Honor turns to me. "Do you

know the people who own the land?"

"Sort of."

"What are you going to say

to them?" she asks.

"I'll just ask them if they

mind us firing off a few shells behind their house."

"In the dark," Robertson adds.

"They probably won't even

be home."

But the house in question

has the lights on. It's a small cozy bungalow built among the aspens

and willows. Through the front window I can see the man of the house

helping his son with his homework, the woman and daughter kneeling

by the fire. The man answers the door.

"Hi," I say, thrusting my

hand forward. "I'm Dave Carpenter. I used to camp on that stretch

next to you."

He shakes my hand, smiles,

and holding his pipe he introduces me to his little foursome. I

explain that Honor and I and a couple of friends want to try out

our shotguns on a few clay pigeons, shooting into the dunes, of

course. My neighbour, who has never seen me until this moment, glances

nervously at some-thing in the kitchen. He seems to be gauging the

distance between his front porch, where we stand, and his telephone.

He strokes his chin, peers at my car.

"Hmm," he says.

But sanity prevails, or something,

and my neighbour shows us where to drive out to the dunes in the

dark. I take my little Toyota to the top of a small sandhill and

point the headlights at a dune about seventy-five feet away. We

will release the clay pigeons with a little hand launcher that looks

like a long sling shot, aiming these at the small hill in front

of us. There is no dwelling in this direction for miles, so the

set-up seems safe, if a little unorthodox. I let fly with a few

while my friends load up. The clay pigeons are black and yellow

discs about the size of a small dessert bowl. They glide like accelerated

Frisbees into the beams of light and out again. For about three

seconds they are visible.

"Gotta be kind of quick,"

says Robertson dubiously.

He goes first.

"Ready?" I call out.

"Ready."

I send one out a bit high.

It skirts the very edge of the headlight's beams.

"Try again."

"Ready?"

"Ready."

I send one across the beam

and this time Robertson manages to get his gun to his shoulder.

"Little low?"

"Yeah, try one medium height,

straight away."

"Okay, ready?"

"Ready."

This one wobbles in flight,

but it's just where Robertson wants it. He fires and misses.

Calder tries. The same thing

happens. Robertson tries again. The night reverberates with shotgun

blasts followed by “shit” or “Next time send er

higher.” Honor tries and nicks one. I try, but no luck. Then

Calder, then Robertson. The little yellow saucers pass in and out

of the headlights, untouched, safe as UFOs. No one scores a direct

hit, but after half an hour of this, we all have a feel for the

gun's recoil, and where our safety catches are, and what not to

do with a shotgun among friends, so we head back to town. When I've

dropped everyone off I discover that my car doorjambs are sticky

with dozens of rose hips.<

SEPTEMBER

24

Raymond Carver is inspecting a hunting licence in my kitchen. "I

am Lee Henchbaw," he says, "and I am from Sass-katchewan."

"No," says Honor, 's's-katchew"n.

You don't pronounce the first and last "a"."

Carver looks up from the licence. "My name is Lee Henchbaw and I

am from Skatchewan."

"S's-katchew'n," says Honor.

"S's-katchew'n," says Carver.

"I am Lee Henchbaw and I am from S's-katchew'n." He smiles. "Eh?"

This is the first time I've

participated in giving lessons in spoken Canadlan: the interrogative

"eh" at the end of declarative sentences, the tightlipped "ou" sound

that rings Scottish to American ears, the clipped syllables through

a puckered mouth, the irresolute shift of the eyeballs as if to

ask if life were a federal or a provincial responsibility.

"Have the geese come south?"

asks Richard Ford. His south sounds like sowth to my ears. There

is a trace of Mississippi in his volce.

"South," says Honor, "with

the mouth contracted. Pretend you're ashamed of your teeth."

"Sewth," says Ford.

"Sewth," says Carver.

"No, south. Don't open your

mouth so wide."

"Mewth so wide," says Ford.

"My name is -"Carver peeks.

"My name is Lee Henchbaw and I am from Sass-katchewan."

"Fantastic," says Ford.

"Oi," says Honor.

A lot of geese are down, I

tell them. Honor and I have heard them going over for the last three

nights, wave after wave.

"Now, Dave, how is this going

to happen?" Carver asks. He and Ford are very keen. The thing that

makes a spaniel strain at his choke collar is in these guys.

"Pits," says Peter Nash. "A

guy name Jake will dig them for us."

Nash is a bearded physician

I have known since I was six or seven.

Like Richard Ford, he's in very good shape. At every birthday party,

Nash was the kid who had twenty-five per cent more laughs than anyone

else. He is still that way. Becoming a father and an ophthalmologist

have not visibly altered him. His preparation for this trip meant

buying and reading all the books by Carver and Ford he could find

in Vancouver. He's as keen as they are. There is an excitement here

among us that keeps building. I know that I will scarcely sleep

tonight.

"You guys call em?"

"Jake does. He knows what

he's doing."

Even though she isn't coming

on the hunt, Honor's face is all aglow. She has lived in six states,

and it seems to me she has missed the sound of American voices.

As most Canadians know, Americans are anything but ashamed of their

teeth.

The deal is this: I will take

Ford and Carver goosehunting if they will give a joint reading at

the University of Saskatchewan for a drastically low fee, what you

might call the best kind of free trade arrangement. I have written

to the Saskatchewan Minister of Fish and Wildlife to waive Carver

and Ford's alien status so that they can hunt in this area right

after their joint reading, rather than wait around for six days

with nothing to do. The reading is slated for September 25th, but

around Crocus, Saskatchewan, Americans aren't allowed to hunt until

October 1st. Duke Pike, the minister in question, is a circumspect

man who believes the universities and intellec-tuals are out to

get him, or so people have told me. Predictably, our request is

denied. Mister Pike suggests we re-schedule the whole damn event,

which at this point is impossible.

I had to get two extra hunting

licenses. Enter Art Sweet and Lee Henchbaw, both writers. They haven't

hunted a day in their lives, but for the cause of literature, they

put their asses on the line. Art Sweet, among other things, is a

very fine one-handed guitarist. Emergencies seem to be his stock

in trade. Lee Henchbaw is a possessed poet; he seems perpetually

astonished by life. He handed me his hunting licence and announced

his intention to write a Raymond Carver poem. Perhaps Carver will

write a Lee Henchbaw poem. Lee is beset by verbal overload. He may

burst before he jumps on his motorcycle.

"I am Lee Henchbaw, and I

am from Sass-katchewan," says Carver, all night long, through a

bout of insomnia.

THAT'S

THE PART I remember from Wednesday night. What Honor remembers is

quite different. None of this talk about goosehunting. She remembers

Nash at the stove frying a large batch of fresh-caught smelts in

egg and bread-crumb batter. She remembers a series of confessions

during our meal. Ford was first: "You know the last words my mother

ever said to me? She was on her deathbed. She said, ‘Richard,

will you please stop asking me all those questions?’" This

remark inspired other confessions about pain, death and worry. Carver

talked about how terrified he was when Tess Gallagher (his partner)

had to have an operation for cancer. Nash told us about his fears

upon discovering an advanced melanoma on his right arm. I'm sure

I put in my two cents worth. In my youth I was very enthusiastic

about pain.

Just before we fell asleep, Honor marvelled about the evening's

talk. "Here's four guys, none of them trying to sound liberated,

talking about their feelings." She was still all aglow. "I've gotta

tell Lorna."

SEPTEMBER 25

From

B.C. to Western Saskatchewan there is a hurricane warning, rare

for these parts. In Lethbridge it has rained four inches; in Calgary

it has snowed twelve. In Saskatoon the wind buckles the elm trees

near the campus and dismantles election campaign signs. For the

first time in Saskatchewan history, there are New Democratic Party

signs on the lawns of the wealthy. The rain has turned to sleet,

but not yet snow. Carver and Ford are having lunch down the street

from my house, Nash and I making sandwiches for the road, when the

phone rings.

It's Honor at her studio.

Jake's been trying to get hold of me. He thinks we should cancel

the trip. I tell Nash. He can see I'm very worried; I've got that

why-me look.

"Let's not phone Jake," he

suggests. "Let's pretend we never got the message. Let's just go."

"Yeah." Desperate dilemmas

require desperate solutions.

We stare at each other. The

reading is two hours away. Perhaps more than a hundred students,

writers, profs and book lovers will be getting ready to brave the

storm for this event. I am holding my head in my hands, moaning

something about the unfairness of life. In Saskatchewan that often

means weather. I rail for a while, and Nash, undaunted, counters

with his own philosophy: that life is random, not fair or unfair.

"The test is always how well

we deal with the randomness!" he cries. He's in an impassioned state

of inspiration, like the wind outside. We seem to be caught in the

plot of a Russian novel here.

We decide to phone Jake. Jake

says exactly what I had feared: "Yiz guys better call the whole

thing off, eh. I mean my brother an I we can't even get a four-wheeler

into the field, dig the pits. You can't get no vehicle no-wheres

near there."

"Jake, I can't call this whole

thing off. These guys have come a long way."

"Well, I dunno what I can

do. We got two inches a rain down here in the past twenty-four hours.

Fields an roads solid gumbo."

"Are the geese down?"

"Yeah".

"Could you show us where they're

flying?"

"Yeah, but yiz'll all have

t'walk some."

"What's the forecast?"

"Pissin."

I look at Nash, who holds

a knife heaped with mayonnaise in one hand, a slice of bread in

the other. He does not seem rattled. "Well, Jake, we're coming."

This is one of those days

when you simply worry your way from one decision to another. I will

worry about the reading till it's happening, worry about not telling

Carver and Ford that Jake wanted to cancel, worry about the condition

of the highway, worry about the sufficiency of everyone's rain gear,

hit the sack and worry about how to get to sleep. I will worry about

setting back Canada/U.S. literary relations by twenty years and

giving Saskatchewan a bad name. In my dreams my parents will tell

me that they told me so, and I will worry about where they went

wrong with me. I am leading five guys to their death. I will really

worry about that one. Outside, the wind howls, the rain lashes,

and life's randomness proclaims itself all day long.

THE CLASSROOM

is full, hushed. People's foreheads, hair, and coats are streaked

with rain. The linoleum is splattered with mud and yellow elm leaves.

We can hear the wind outside, and this sound precipitates, it seems

to me, a cozy smug feeling. The best writers and some of the best

artists in the province are here. A contingent of twelve people

has driven all the way from Regina against this wind and into the

sleet. The classroom seems to bristle and glow. People are still

gasping from that last dash across the quad. Guy Vanderhaeghe (My

Present Age) is chewing a huge pink wad of bubblegum. Barbara

Sapergia (Foreigners) huddles into her coat and breaks

out in little shudders. Pat Krause (Freshie) and Byrna

Barclay (The Last Echo) babble about how cars were swaying

in the wind fifty miles south of Saskatoon. Anne Szumigalski (Dogstones)

spreads her wool shawl out around her like a tea cozy, and she smiles

her four year old girl's smile. Patrick Lane (Linen Crow, Caftan

Magpie) looks straight ahead as several women talk to him.

"You better believe it," he says. "You better believe it." Geoffrey

Ursell (Perdue) strokes his beard, folds his arms, surrounds

himself with reflective silence. Lois Simmie (Pictures)

looks at Carver with undisguised adoration. Elizabeth Brewster (Selected

Poems, 1944-1984) hurries in at the last moment, huddles into

the last available chair. Lorna Crozier (The Garden Going On

Without Us) is the last one in the room to stop laughing. Art

Sweet (fiction writer, one-armed guitarist, poet) and Bob Calder

(Rider Pride) look as though they are seconds away from

opening kickoff. And (words bouncing off his brain like ping-pong

balls) Lee Henchbaw is perhaps thinking, I am Raymond Carver and

I am from Port Angeles. Nash's head goes around and around three

hundred and sixty degrees so he can see everything. This is show

biz and he knows it. Bill Robertson (Standing on Our Own Two

Feet) gawks impatiently, as though he wants to get in a dozen

windsprints before the reading begins.

"Ladies and Gentlemen," I

begin. My voice seems to be talking and I'm helpless to do anything

with it. "I suppose I was hired on here because I am a regionalist.

That means I'm interested in the writing that has been done around

here. Well, angling for Raymond Carver and Richard Ford has been

a very good exercise for me, because I'm now willing to admit that,

yes, some very good writing is going on outside of Saskatchewan."

Polite laughter.

Get on with it, Carpenter.

Carpenter (Jokes for the

Apocalypse) gets on with it. A warm applause, at long last,

for Richard Ford. He is lean, pale; his face flickers with sensitivity.

(Elizabeth Brewster confides later to me that he certainly is "cute".)

His voice has gathered intonations from all his wanderings, from

the Deep South, to the industrial Northeast, to the Midwest, and

to the Old West, where he now lives.

I was

standing in the kitchen while Arlene was in the living room saying

goodbye to her ex-husband, Danny. I had already been out to the

store for groceries and come back and made coffee, and was standing

drinking it and staring out the window while the two of them said

whatever they had to say. It was a quarter to six in the morning.

This was not going to be a good day in Danny's life, that was clear,

because he was headed to jail.

Thus

begins "Sweethearts", Richard Ford's latest story in Esquire (August, 1986). For half an hour, the audience wraps itself up in

Richard's story and wears his voice like a comforter as the wind

buffets the window panes. It occurs to me that being read to is

a great luxury, especially on a stormy day. The audience responds

warmly, and I wonder if the public Carver can be half as captivating.

On the page, of course, he is, but this is show biz.

Raymond Carver stands six

feet two, a bigbodied man apparently comfortable with his size.

He has a way of going quiet and quiz-zical, and at such times reminds

me of that awkward brainy kid in grade six. Or as an undergraduate,

he would be the shy, dis-hevelled guy in the corner, lost in thought.

A bit like Lee Henchbaw. They both have an abundance of curly hair

which I envy, and it seems to announce something luxuriant in their

minds that cannot stop growing. They are working class men right

down to their cigarettes. Both recall hard times and domestic strife

all the way back to childhood. But the man at the lectern has now

become Raymond Carver, and Lee is perhaps fifteen years away from

becoming Lee Henchbaw. His first poems have just appeared, but he

is still young enough to ride a motorcycle. In a few years, he will

be up there at the lectern, launching one of his books. In a few

more, if he remains devout and disciplined, he will become a small

part of literary history. Then fade with the rest of us. Clay pigeons

flashing through the headlights of the Cosmos. The critics take

their pot-shots in the dark, and usually miss, and then we all die.

I wonder if Nash would agree with this. The weather breeds such

ruminations.

Carver is absolutely unhistrionic,

soft spoken, humble by disposition rather than design. He begins

by asking the people at the back of the room if they can hear. But

perhaps they can't hear him yet, so they just stare back at him.

He asks again. They stare back again. Carver is in Saskatchewan,

where seldom is heard an extrovert's word. People in readings don't

raise their voices if they are in the audience. That would be showing

off. So Carver begins, plainly worried. He reads from one of his

recent New Yorker stories ("Whoever Was Using this Bed,"

April 28, 1986). In about one minute, with the line, What in God's

name do they want, Jack? I can't take any more! he has us. Soon,

more than a hundred sodden people are howling with laughter. The

characters grope through the night for words to put on their fears

and their despair, but through-out the story there is this laughter.

I can't help wondering, is this the man Madison Bell attacked (in Harper's, April, 1986) for being a "dangerous" influence

on American short story writing? Another studiedly deterministic

nihilist? Bell argues that the reader is drawn into a Carver story

"not by identification but by a sort of enlightened, superior sympathy."

The audience here goes from rib-aching hysteria to rapt attention

as the narrator and his wife talk in bed at five or six in the morning

about whether one would unplug the other from a life-support system

if s/he were suffering unduly. Is this conver-sation the sort of

thing the genteel Mr. Bell would call nihilistic? Am I missing something?

When I read Cathedral (upon which Bell focuses his attack),

did I miss out on all that impoverishment of the human soul? Maybe

like Bell I should have been saying to Carver's characters, "I understand

the nature of your difficulty; how is it you don't?"

I decide, at the moment of applause, that the genteel Mr. Bell suffers

acutely from a superiority complex and that he wouldn't know a compassionate

story if it goosed him in the subway. This, of course, isn't exactly

a meditated judgement, only a reflex. But I can't escape the conviction

that Carver is telling our story, however squalid or despairing,

and we find ourselves having slept in his narrator's bed. The applause

continues for a long, long time. You’d think Tommy Douglas

had come back from the grave.

The crowd ascends to the 10th

floor coffee lounge and descends upon the Americans. They have to

clutch their styrofoam cups close to their chins, and guard them

with the other hand. Saskatchewan has come to pay court to them.

The mood is suddenly effusive.

In fact, for this place at

least, it is wildly effusive. I feel like one of those Broadway

producers who chews on cigars and shouts at the last minute replacement

for the leading lady, "Go out there, Mabel, and break their hearts!"

My God, I keep thinking, I've got a hit on my hands.

An hour later it occurs to

me that I have a hit and no pits. No pits, no geese. No geese, no

reciprocity from us to them. Carver and Ford have waived a considerable

sum in fees and expenses to come here and shoot. Which makes me

(in collusion with the weather) one of the alltime welchers in Canadian

literary history.

"SAY,

AH, DAVID," says Carver in the front seat, "that's a heavy rain

coming down. Is that normal for here?"

"Well, no, Ray. Actually it's

a real heavy one."

He looks out at the countryside

flashing by in the fading light. Ford is silent. Perhaps he is looking

for geese. So far we have seen none.

A minute later, Carver says,

"Say, ah, David, that's a heck of a wind out there. Is that normal?"

"Well, no, Ray. Actually it's

quite unusual for up here." I've said nothing about the absence

of goose pits or Jake's phone call. I've said nothing about the

hurricane warning. The one blessing is that this pummelling wind

is behind us.

"About these pits," says Ford.

"Aren't they likely to be a bit on the wet side?"

I tell a censored version of the grim facts. There may be no pits

at all. There can't be any digging in the farmers' fields until

they've managed to take in their crops. And in this weather, digging

is impossible, walking "a bit dicey." I suppose my nervousness has

begun to show through.

"David," says Carver, "I'm

excited. Richard here is excited. I feel I'm on some sort of adventure.

If I even see some geese tomorrow and get a bit of walking in, that'll

be fine. I'll have had my fun. So don't worry. Hell, we're all on

an adventure here."

I nod, very much relieved,

and repeat Nash's words on contending with the randomness of life.

This view, the kind of advice an ophthalmologist may have to give

to a patient on occasion, rides well with us all the way through

the storm and down to Crocus. Nash is no doubt spreading his gospel

of adventure in Calder's vehicle. The six of us have become soldiers

of fortune. We face the howling infinite together. This last statement

probably sounds self-dramatizing. Such is the language of epic.

SASKATCHEWAN AND CARVER. Why the instant love-in? He's a fine writer,

but many other fine writers (Margaret Atwood) and scholars (Northrop

Frye) have bombed in Saskatoon. First we single out Carver's books

for praise, then, in about two minutes of reading, we respond just

as warmly to the man. Better readers (W.O. Mitchell, Erin Moure,

Graham Gibson, Michael Ondaatje) have worked harder to warm up an

audience. And wasn't Ford's story a bit tighter? It seemed so during

the reading.

Should we not, then, be more

circumspect about Carver's books, such as Mr. Bell has advised?

Some of us are no doubt aware of Carver's excesses even as he reads,

but no one voices any critical disapproval later on, after the event.

Is the Carver/Ford reading one of those obsequious moments, then,

in which a bunch of Canadians grovel at the feet of someone who

has made it big in America? I can't absolutely deny there was at

least a trace of this feeling in the room. But I don't think the

excitement at the reading was impelled by mere obsequiousness. I

think much of the laughter, for instance, was that of recognition,

that the agonies of Carver's two insomniacs, their dread of a prolonged

death, were to a great extent our own.

Mr. Bell seems distressed over the language of many Carver stories,

concerned as they are with "the predicaments of bluecollar workers

verging on the skids." What rankles at Bell's sense of literary

propriety "is a slightly artificial lowering of diction" to "describe

a very sophisticated pattern of events."

I find this argument irksome.

I read Carver's stories for

many things: among them that strange dependency of squalor and humour

in the tone, the equally strange dependency between the ordinary

and the numinous, and that way his characters have of telling us

far more than they mean to. Who says this is an artificial lowering

of diction? Is it artificial because plainspeaking people are not

generally competent to talk about the complexities of their lives,

or at least report their own stories in a suggestive way?

Carver brings to Saskatchewan

the suggestive richness of plain speech. Saskatchewan greets Carver

with a tradition of plain-speaking. Our greatest works of fiction

(Sinclair Ross's As for Me and My House, W.O. Mitchell's Who Has Seen the Wind, Wallace Stegner's Wolf Willow , Guy Vanderhaeghe's Man Descending, for example) are unapologetically

realistic. Perhaps this adherence to the imperatives of realism

doesn't seem surprising to readers unfamiliar with the Canadian

West. But if we look at the finest Alberta fiction over the same

fifty years (Howard O'Hagan's Tay John, some of Rudy Wiebe's

Indian stories, most of W.O. Mitchell's Alberta fiction, and Robert

Kroetsch's Badlands, for instance), we get myth, epic,

tall tales and other kinds of comedy in the hyperbolic tradition,

romance, postmodern satire-anything but realism. When Albertans

were forging the Social Credit Party out of the remains of the United

Farmers Movement and the biblical prophesies of William Aberhart,

Saskatchewanians were creating the C.C.F. party. Compare the mythopoeic

style of Aberhart's or Manning's speeches (in church or in the Legislature)

with the hardnosed realism of Tommy Douglas' speeches, and you have

a rough idea of what I'm talking about in the literature of these

neighbouring provinces.

Nowhere I know of are the

niceties of middle-class diction, the borrowed jargon of deconstructionism,

the linguistic excesses of romantic fiction less relevant than in

Saskatchewan literature.

And in Carver's stories, I

suspect. There is a correlation here, and it shows up in the language:

the rhetoric of hard lessons, limited expectations, toughminded

compassion. We have known hard times and from this knowledge comes

our regional pride. Western Albertans are mountain snobs, Vancouverites

like to feel sorry for the rest of Canada, Victorians are flower

garden snobs, Calgarians (to use some of W.O. Mitchell's distinctions)

are horsey snobs, Edmontonians are sports and progress snobs. Saskatchewanians

are for the most part endurance snobs. They are sure they can endure

more drudgery, worse winters, more absurdities from Ottawa, worse

droughts, a greater sense of nullity from looking at flat surfaces,

more defeats to their football team, than anyone else in Canada.

Saskatchewan literature, as

Robert Kroetsch has said(perhaps lamented), is inward looking. The

experiments of Marquez, Borges, or Barth or Calvino, which were

emulated and imitated by so many writers in other parts of Western

Canada, came to nothing in Saskatchewan. At their best, Saskatchewan

writers like Lorna Crozier, Andy Suknaski, Guy Vanderhaeghe or Ken

Mitchell preserve a strong connection to their regional origins.

So have Sinclair Ross, John Newlove, and a number of eminent former

residents. The language of postmodernism seems to be of passing

academic interest, having so little to do with Saskatchewan idioms,

in our mouths an artificial language. The complexities of our lives

are rendered in a native language; the complexities of our collective

imagination are rendered in terms that emerge from our own dreams

of our place. We are stolidly unimpressed with whatever happens

to language when it gets deflected and convoluted by life in the

big city. There are some important exceptions to this overall picture

(the poetry of Ed Dyck and Anne Szumigalski, the fiction of Geoff

Ursell), but even these three mavericks have written extensively

and successfully out of their Saskatchewan experience. There is

still a grainy, marshy smell to some of their most adventurous work.

For the most part, we are

plainspeaking, and this explains to me the recent popularity of

Carver's visit. He managed to affirm something about our own idiom

by speaking so well in his.

ROBERTSON

GOES from room to room in his underwear. Rallying the troops. "Five

thirty tamorra mornin," he growls. He sits on anyone's bed, at home

wherever he goes. "Hell," he says after a pause, "it'll be just

like summer camp, first night. We'll all stay awake an talk about

sex."

The wind shakes the basement

windows as we sit around, the rain seeps in and sprays anyone beneath

the screens. We lay out our rain gear, our long range magnum shells.

The geese will be flying high, spotting us easily. Carver and Ford,

both insomniacs, will room together, Calder with Robertson, and

I with Nash. Carver wants to be roused by five. He has a little

coffee maker and wants to get it going so we can all have a shot.

Nash warns me of his snoring, claims he can shake a building with

it. He tosses me some earplugs.

Maybe Robertson is right.

It is a bit like summer camp. Nash sleeps like a baby, but I review

the day, try to think about lying in mud, revel in the success of

Ford and Carver's reading, blink and ruminate all night long. Perhaps

I doze for half an hour, but when the alarm goes off at five, I'm

as galvanic as an electric owl.

SEPTEMBER

26

Five o'clock in the morning. Ford mumbles, "Why the fuck do we have

to get up so early?" He sounds very much like a boy in Mississippi

embarking on his first hunt. He will demonstrate later that he is

anything but a greenhorn.

Ray makes pot after pot of

strong filter coffee. Each pot is a cup. Each cup gets passed from

room to room, from bed to bed. The empty cups come back to Ray and

he has another to send down the line. Breakfast is doughnuts, several

kinds. This is our gift to Ray, because apparently he is addicted

to them in the morning. Our rooms are littered with crumbs and spattered

with coffee. We drag on our clothes, layer after layer. I start

with long johns, then thick pants and T-shirt, then K-ways top and

bottom, then thick wool sweater, then canvas hunting coat and hat.

Most of what I wear is what I've worn for decades on these trips.

My pants are torn, my coat stained and stiff with goose and duck

blood. Calder looks about the same to me, and Nash and Robertson.

We reek of barley and odd prairie smells. An old fellowship seems

to re-emerge with the donning of this brown canvas coat.

Carver and Ford have newer

waterproof clothes, and Ford actually looks dapper in his. We'll

have to do something about that, I think, but I can't imagine what.

Guns in hand, we lurch and waddle through the rain and mud to Jake's

house. He meets us with a friend in his garage. It is brilliantly

lit inside. He too has doughnuts and coffee, knowing of Carver's

addiction.

"She's colder'n a sonofabitch

out there," says Jake. "Sock 'er down, eh? It's a long time till

dinner."

The garage is huge, full of

duck-hunting equipment and all-terrain vehicles. The lighting is

so intense that we stand around in embarrassed silence, yawning,

savouring the last dry surfaces we will feel for many hours.

Four of us go in Jake's jeep,

three follow in Calder's truck. We take the highway about ten miles

south past the town of Horizon, and Jake pulls over and parks on

the shoulder. "Far as she goes," he says, knowing full well that

nothing with wheels could get a hundred yards on the side roads.

The sun makes faint grey streaks

on the eastern horizon, but it's still dark where we sit in the

jeep. Suddenly we stumble out onto the road, Jake in the lead, swearing.

"Timed er wrong," he says. “Shit.”

I hear choruses of falsetto

barking, and then I see them: wave after wave of geese lifting off

the slough and pouring over the road, low but out of range. The

sky is exploding with them: greater Canadas, lesser Canadas, specklebellies,

snows, and many ducks.

We lurch down the road in

single file. We are almost at the edge of the flight path, but it's

getting lighter and there is no place to hide. The mud builds up

around our boots until each foot wears ten pounds of Saskatchewan

gumbo. Our breath comes hard. The wind and rain lash into our faces.

My glasses need windshield wlpers.

Jake and Ford and I manage

to reach a point on the road about a half a mile down from the vehicles.

Jake and Richard begin to blaze away, standing on the road. I have

only a sixteen gauge, so I keep on trudging into the middle of the

flight path, Nash right behind me. I hear guns going off but I keep

on going till I reach a culvert I can hide behind. Nash and Ford

fire down the road and double on their first goose. A lone duck

tries his luck swinging low over the culvert, and I bag him. He

falls on the road with a squelch and he's dead before I stuff him

into my coat pouch. This is how you always want it to happen, a

clean kill.

Calder and Robertson are nowhere

in sight. Jake has headed back into town. Carver and Ford lie in

the ditch back down the road two hundred yards from me. Nash trudges

slowly out into the north field and disappears over the edge of

the world. It is every man for himself, and the birds are wise to

our plan, such as it is. They spot us a mile off and fly high over

our heads. We blast away and they keep on flying. This is called

pass shooting. The geese pass, the hunters fail.

By nine o'clock we still have

only a duck and a goose, apparently dispatched by Calder as it tried

to escape. This I learned later; Calder and Robertson are still

missing in action.

The wind has been playing

with us as we lie in the mud. By ten o'clock it rises up like a

Wendigo and blasts sleet and rain into our faces. To remain as innocuous

as possible, Ford and Carver lie face down in the mud, and when

the geese fly over, they leap up and try to fire as their feet slide

beneath them. I shoot occasionally, but it's clay pigeons in the

dark again, so I huddle down by the culvert to try and keep my back

to the wind, checking every minute or so for new flights of geese.

Nash reappears over the northern horizon like a perambulating scarecrow,

then disappears. He moves to keep warm.

At last the wind and sleet

are unbearable, so I head for a clutter of grain bins out in the

field. Crouching behind these bins is a bit better, but I'm still

so cold my teeth chatter. One of the bins is actually an old wooden

grainery. I peek inside. It is empty, which surprises me. But because

of this weather, half the farmers haven't been able to harvest their

grain, thus the empty bins. I turn the handle and go inside, and

at last, with the wind shrieking all around the bins, I begin to

warm up. From time to time I can hear geese flying over the bins

but my gun leans against the wall. This soldier has bid goodbye

to the wars.

Then I smell something, an

offering from below, sour and rotten. Skunk. I'm out of there in

about four seconds and back to my culvert.

By eleven Nash returns, three

large geese and a duck hanging over his shoulder. He is tired, happy,

and very wet. We push on down the road. Carver and Ford get up out

of the gumbo, and I see now what they are made of. From lying face

down in the mud, Richard has acquired a carapace of bluish clay

over his face. His clothes are filthy. Carver is just as muddy,

and he is bleeding rather badly from two cuts in his left hand.

We look each other over for a while. We are the remnants of a defeated

army, trench warfare, circa 1916 when the Americans entered the

fray.

And the Americans haven't yet admitted defeat. First Carver, then

Ford, then I, begin to build a large duckblind out of chaff. I gather

the chaff, hand it to Richard, who gives it to Carver. Back and

forth we go, the geese flying cautiously high. By noon we have what

resembles a huge bird's nest, big enough for three hunters. Ford

and I are puffing, Carver close to exhaustion.

It's time for lunch. We shoulder

our guns and slowly trudge the long mile to the vehicles. Robertson

and Calder greet us by the truck. They've had no luck at all and

seem discouraged, especially Calder. When he had to dispatch the

wounded goose by wringing its neck, he discovered something about

himself. Over the twenty-three years between this hunt and his last

one, he had acquired a conscience about killing things. We discussed

this later. We all shared a real affection for those geese we hunted--apart

from their value as food or quarry. This affection is what Faulkner

refers to as loving the creatures you kill. But Calder's conscience

took him one step further. The killing felt unbearable to him and

he had lost the hunter's instinct.

On our last fishing trip, Calder had always been the driving force,

the keener, the strongest courier over the last portage. I had been

the one to lose sleep worrying about bears and the first to tire

after a portage.

"Can't cut er," says Calder,

plainly discouraged.

"But Calder, you've been an

administrator. You've been in the dean's office for God's sake.

You're not supposed to have a conscience any more."

He gives me a sardonic grin. There is nothing more to be done. Like

prehistorlc creatures who dimly feel the end of their epoc, we slither

into Calder's camper and head home for lunch. Some of them curse

Jake, though it's not his fault. We curse the weather and dream

of showers and more hot coffee.

While the others shower, I

head over to Jake's garage and find him in the grease pit. Four

other guys stand around talking with Jake as he works. I'm carrying

the four geese and two ducks. "Where can I get these cleaned?"

"Goose plucker's daughter,"

says an old fellow. "Over at Horizon."

"Does she work fast?" I ask.

Jake sticks his head out of

the grease pit and smiles. "Oh, she's fast all right."

The men chuckle.

"You go t'Horizon, Dave. Doris'll

take care of ya."

Again, tribal chuckling from

deep in the belly.

"No crap, Dave, you're gonna

meet a real pretty girl, eh?"

By the time I get back to

the motel, some of the guys are eating, some showering. When it's

my turn, I simply hold my K-ways and canvas coat under the shower

until the clay peels off and down the drain. The bottom of the shower

is plugged with three inches of mud. Changing into dry clothes is

a pleasure worthy of a voluptuary.

Finally, after lunch, as the

others rest, I load up the birds and take along Robertson for protection.

This Doris woman sounds threatening to me. I've turned her into

a monster of Gothic proportions in my own mind, and Bill is very

curious. He assumes she is merely old or disfigured.

Horizon is a ghost town. Two

families remain. It used to have hundreds, but bad crops and large

farm corporations seem to have driven out the residents. Doris'

place is a one story frame shack next to a demolished house and

barn on the edge of town. Her back yard is the endless prairie.

I think of Mrs. Bentley from As For Me and My House, how

each day she would listen to the wind and dust sift through her

house. At one point she calls the wind "liplessly mournful." I don't

understand this phrase, but it haunts me.

I knock on the door.

Doris answers. She is about

five foot two, ash blond, twentyfive, her makeup a bit on the heavy

side, barefoot, and gorgeous. "Hi," she says with a bright smile.

AT THREE

o'clock, fed and rested, we cram into Calder's camper and try our

luck again. We park the truck by the road again and off go Nash,

Ford and Robertson. Nash will stick to his perambulating; Ford and

Robertson will crouch in the duck blind.

Carver tries the muddy road

again, but it's no go. He has a torn muscle or a charlie-horse in

his left groin, a bum right leg, a swollen left toe, and from compensating

all day long, a bleeding blister on his right foot. We've helped

him bandage up his hand and his foot, but the man is on his last

legs, sweating and hobbling in the mud. "You know, Dave, I think

if I try this road again I'm just not gonna make it. I think maybe

I'll stick by the highway."

We stop and look around. The

other three have gone on ahead and disappeared. The rain has almost

stopped but the wind persists. "I think I'll stick by the highway,"

he says again. "I think I'll try my luck here." A while later he

says, "I tell you, Dave, I could sure use a Coca Cola. Where do

you think we could get one?"

I have the keys to Calder's truck. There is Horizon and Bean Coulee

just a few miles down the road, and of course Crocus in the other

direction. We head for the truck.

"If I could have a Coca Cola," says Carver, smiling painfully, "I

think I could maybe make it through the afternoon." Perhaps this

is how Carver talked about booze in the bad old days before he took

the pledge. I too am thirsty. Before us looms a huge frosty bottle

of Coke. The prairie has become a desert, and that ultimate American

symbol, the Coke machine, our oasis. By five o'clock or so, we are

beat but we simply will not acknowledge this. Like I say, Horizon

is a ghost town. We discover it has no store. Bean Coulee hasn't

even a Coke machine. We head back toward the muddy road, thirsty

as hell. But before we reach it, Carver spots a huge wedge of geese

flapping over a gravel road. A gravel road. This means it can be

driven. We try it out. The truck moves slowly down the road; wet

though it is, the tires grip. We drive beneath another large flock

of honkers. Carver clambers out and checks the ditch. It's almost

too dark to shoot, but we have tomorrow morning. Carver and I discover

ample patches of weeds and standing grass, deep patches where we

can hide in the morning. There is a light in Carver's eyes, a youthful

look. "Goddam, David, this is it. We can come here tomorrow morning.

Five o'clock. This is the place. Would you like to join me here

tomorrow morning?"

"You bet," I say. "If they're

flying low, I'm with you." My gun is built for close range stuff,

so we seem destined to try our hand at this new road. To the north

are several huge fields of swath. To the south across the road is

a large slough, and string after string of geese pouring into it

from the fields. The whole dark sky is honking.

"You bet," says Ray. "This is it. This is the place. You know what?

I'm comin here tomorrow morning. Would you like to come?"

WE ARRIVE

AT DARK on the mud road to pick up Nash, Robertson and Ford. The

latter two are waiting with big smiles on their faces. They each

have four geese. Ford has been coaching Bill. These are his first

geese ever. Robertson is the most talkative man I've ever hunted

with, but as he loads his geese in and helps with the others, a

strange aura of silence has fallen over him. Like his little two

year-old boy, Jesse, he just grins a lot as though the world has

come to honour him.

Nash is a mile in again, and

I have to go and get him in the dark. The more the mud balls up

around my boots, the more tired I get. It's dark out now, but at

least the rain is gone and the stars are out. We meet on the road

where Nash has been listening to the geese. He has long since given

up shooting. The flocks are pretty much all back on their water.

Nash has been counting strings of geese. He figures there may be

as many as fifteen thousand in a slough of scarcely more than a

dozen acres. Goose shit surrounds the slough like cigarette butts

at a race track. And the sound is incredible: falsetto cackling,

like a convention of auctioneers. When I yell to Nash across the

road, he can't even hear me.

THAT

NIGHT in the bar we have a pizza supper. We're all sleepy, so the

talk has hit the drowsy stage by the time we reach the presentations.

Calder and Robertson present Carver and Ford with official Crocus

tractor caps. Nash presents them with Wayne Gretzky tractor caps.

I toss them each a bag of Saskatchewan books and deliver a little

speech. The idea is, if one of their literary colleagues says, "What?

Serious writing in Saskatchewan?" they are to respond either with

violence or one of the above-mentioned books. Ford and Carver are

visibly touched by these presentations but even more moved by their

need for sleep. We all hit the sack before ten o'clock.

By this time Doris has done

twelve geese and two ducks for us. They've all met her and been

smitten. She sits in a shack in a ghost town and flies through our

dreams. Not too long from now, we will read each other's stories

or poems with Doris as the muse. All through the storm, I imagine,

she is listening to the wind. All day long we've been lying in the

mud or shooting off boxes of shells at the indifferent gods, unaware

that the muse was waiting for us....Amused by the muse...abused

by the muse...but none too clever to...refuse the muse? These things

dribble from my lips as I fall asleep to the thunderous applause

of Nash's adenoids.

SEPTEMBER

27

Five o'clock, still pitch black out. I knock on everyone's door.

Carver makes coffee, but this time there are only a few crumpled

two-day-old donuts for breakfast. Calder is going to give it one

more go. He heads out in the truck with Nash and Robertson. Ford

and Carver come with me. Ford managed to bring down five geese,

and he feels Carver should try his gun. Richard has generously decided

to sit this one out. Neither Carver nor I have managed to bring

down a goose, and Ford is eager that we do well this time. We drive

out to the gravel road; the others return to the mud road. The stars

are out and the dawn tilts slowly like a warm cup of tea. There

is not a trace of a cloud. Ford coaches Carver on the handling of

his gun and leaves in my car to pick up our plucked birds. Just

as I'm settling into the ditch behind a telephone pole, the first

wave comes over Carver's head two hundred yards down the road. He

fires twice and two geese fall. One is only winged and takes off

across the field flapping frantically over the swath. Carver leaps

out of the ditch and gives chase. I race over to help him--after

all, he has become one of the walking wounded--but Carver has suddenly

regained his youthful legs. When I get there he sports two large

specklebellies and an enormous grin. "Boy, isn't that something,"

he says.

We hurry back to our separate

positions in the ditch, and over they come again. Carver knocks

another goose down, this time a young Canada. A pair of specklebellies

come at me from the sunrise, just in range. I stand up so that my

body is shielded by the old telephone pole, lead the bird on the

left, and fire. It seems to stop in mid-air and climb straight up.

I fire again and down it comes, my first goose in four years. Carver

waves. Minutes later a large chevron of honkers passes over our

heads out of range, then another flock, this time lower. Carver

fires first, knocks one down, and then I fire and down comes my

first lesser Canada. We chase our birds into opposite fields, bag

them and lurch back into the ditch. It's about nine thirty, the

sun is climbing and hangs in a blue sky over a stubble field filled

with thousands of speckle-bellies, Canadas and snow geese. The geese

tend to feed with their own kind, and so the snow geese stand out

among the darker specimens in blotches of white. Thousands of geese

are still in the slough to our west, and all day they will cross

in waves of a hundred or more from slough to stubble, from stubble

to slough. They fly high now, and Ray and I are extremely visible.

What the hell.

Ford returns in my car, and

with our instinct for show biz still proclaiming itself, we manage

to meet him carrying our geese. He is ecstatic. He wants to shake

our hands but of course they are filled with goosenecks.

"Oh boy!" he yells to Carver.

"You liked it?" he asks, pointing to his gun. That one gun has accounted

for nine geese so far this trip. "And you shot two of these?" he

says to me. "You got two geese?"

I say, "Aw."

The six of us have brunch

in Crocus and gas up for the long ride home. The woman at the pump

asks us how we did and we tell her twenty geese, two ducks. The

weather has been so bad that hardly anyone else has been able to

get to where the geese are. The woman at the pumps tells us another

group of five hunters picked up six geese, but we apparently were

the only ones to do half decently. This for me is a source of enormous

pride. I'll be telling this story for a long time to come. The sleet

will become snow, eventually a blizzard; the edge of a hurricane

will become the eye of a hurricane; the bag will grow from twenty-two

to forty-four; Carver's cuts on his left hand will become an ugly

gash on his left arm....

"Doris took care of yiz, did

she?" says the young woman at the pump.

"Yep," says Calder.

"Oh, the hunters really appreciate

Doris," she goes on.

Calder's ears perk up. All

of our ears perk up.

"Oh, Doris really pulls in

some extra money in huntin season," says the woman with all the

innuendo she can muster.

"No kiddin," says Robertson.

I can see a poem flapping

across the ditch as Robertson gets back into the truck: "The Gooseplucker's

Daughter" by William B. Robertson. How will Carver handle this one?

Will Ford beat him to the punch? Will I?

"There's a dance on tonight,"

says the woman. "You guys should come along."

"We have planes to catch,"

says Nash.

"Too bad," she sings. "Doris'll

be there."

CARVER

HAS A COFFEE and cigarette at the Crocus Hotel café while

the other guys get their gear together. He's in his reading duds

again, surprisingly dapper: a beige raincoat he bought in London,

brown turtleneck and tweed jacket, civilized shoes and slacks that

seem out of place in Crocus. He looks pleasantly tired, a lot like

that author whose pictures are on his dust jackets.

"You look like Raymond Carver,"

I tell him.

I can now confess to him that

Jake had phoned just before his reading to cancel the trip. He likes

that: the fact that we risked our hides against strong odds to come

down here and be boys again.

For most of us, I dare say,

the trip amounted to an adventure of non-heroic propor-tions. It

was six guys wallowing in the mud and struggling with other things

as well: Carver with physical pain, Ford with the unusual cold,

Calder with his feelings about killing things, Robertson with his

old/new gun, and on it goes. It was six guys unaccustomed to mud

and hurricanes trying (metaphorically at least) to shoot pigeons

in the dark. Above all, trying to help each other get through the

day. Ford coached Robertson in the duck blind; Nash and Carver bolstered

my courage when it looked bad for the trip; Calder wired on a muffler

by lying under his truck in a mud puddle so we could all go in the

first place; I ran around being host for several days and worried

for everyone; Carver made something like twenty cups of coffee from

his tiny pot at five A.M.

At the airport, Carver tries

to thank me for a great hunt and gets choked up. I try to tell him

that such rewards are his due because he happens to write well,

but my words come stumbling out for want of sleep. Carver and Ford

both want to come back and stay longer. We're already dreaming of

next fall when great cackling legions of geese in flocks as wide

as Saskatoon will once more descend from the North to fatten up

on the grain fields, reminding us (who shoot at clay pigeons in

the dark) that we were once Lee Henchbaw and we are from Sass-katchewan.