Minding Your Manners In Paradise

Minding Your Manners In Paradise

When

I was a little boy, I had no trouble imagining Paradise in

very specific terms. No angels and saints for me. My Paradise

would look just like Johnson Lake, a small reservoir fifteen

minutes drive from Banff, Alberta on the Lake Minnewanka Road.

It was stocked with rainbow and brook trout that grew prodigiously

fast on big nymphs, snails, and freshwater shrimp and spawned

spring and fall in the feeder stream. I caught my first trout

there and my brother hauled in a 6 pound rainbow at the age

of six.

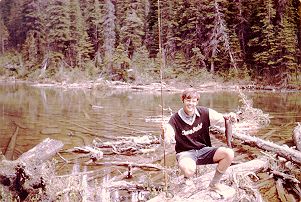

When I was in my late teens,

I used to fly fish there with my friend Peter Hyndman. We came to

Banff to work in the summer partly because of the fly fishing. We

were just out of high school and convinced that at the secret heart

of the unfolding cosmos was nothing but fun. There were more parties

here in one month than we had ever gone to in a year, more unattached

girls than we had ever seen. And one or two nights a week, we would

declare a health night and go casting on the banks of Johnson Lake.

In my first summer in Banff I landed a four pound brook trout and

Hyndman brought in a 5 1/2 pound rainbow. We were becoming legends

in our own time, at least among the trout. The girls were another

thing entirely.

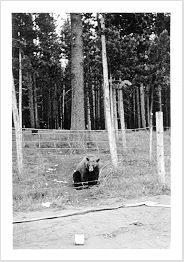

Each summer we returned and took the well worn

trail around Johnson Lake. Always there was wildlife. One night

a very large black bear came down to the lake to drink, or perhaps

to stare at the bizarre fly lines whipping through the late summer

air. The bear came right up to me. I think I detected an air of

disapproval. This was 1960 or '61, and bears were still so common

and innocuous, we hadn't learned to fear them. The bear and I looked

at each other from a distance of perhaps 20 feet. It saw that I

wasn't going to feed it, and so it lumbered into the jackpine. Hyndman

and Carpenter returned to their casting.

A big rainbow was rising just

beyond my fly, so I waded in and tried again. Night was falling

and Hyndman had brought in his line.

"One more cast," I tell him.

This is the most commonly

spoken promise by a fisherman, and the least likely to be honoured.

I threw out a big bucktail right where the trout had been rolling

in the sun-set. I let my line sink and began a slow retrieve. My

bucktail became an escaping minnow. Jerk jerk jerk, and suddenly

the tip of my rod plunged down. A tailwalking olympian had grabbed

my fly. He leapt high out of the water, paused for a moment to defy

gravity, and plunged back in. He took off for the middle of the

lake and my reel whined high and frantic.

"Should I get the net?" Hyndman

yelled to me.

"Yes," I must have said to

Hyndman, "get the net."

Hyndman got the net and waded

over to me while the rainbow cavorted and leapt and took shorter

and shorter runs.

"Don't lose him."

Any non-fisher might think

that this advice was labouring the obvious. But an angler knows

that this is a good luck spell one casts for another.

The rainbow seemed to be tiring.

It was pointed down and tailing feebly into the gravel. This passive

stance allowed me to ease it closer and closer to the net. Hyndman

stretched toward the fish. Dark blue on the back, silver on the

sides with a long stripe of pink. It was more than two feet long.

It was bigger than Hyndman's 5 1/2 pound rainbow. It was going to

be gutted and filled with wild mushroom stuffing and baked for a

gathering of at least a dozen friends. It was going to ingratiate

me with a half dozen mountain beauties and be bragged about for

years to--

Snap!

A side to side motion of its

head, the rainbow's way of saying NO to the dreams of a young man

intent on becoming a legend. Gone. The king of the rainbows tailed

its way back into the deep water as uncatchable as the great white

whale.

One of

the differences between old anglers and young anglers is in what

they tell their friends. We told our friends everything about Johnson

Lake. We even took them there. We took our girlfriends there, bating

their hooks with big juicy worms and nymphs. Our friends told their

friends and their friends told their friends. By the mid-sixties,

this lake, which I felt Hyndman and I had owned, became host to

dozens of anglers a day and one or two wild parties each night in

the campground. You could hear the voices of folksingers and the

sound of guitars and bongos. Always those plaintive undergraduate

voices puling about the misfortunes of picking cotton in the hot

sun or mining for coal. I was one of those folksingers.

I even remember once throwing

a half finished bottle of wine into the lake. Someone had noticed

the approach of an R.C.M.P. patrol car, and I was still under age.

I threw the bottle into the lake in panic and stumbled off into

the woods. The wine in question was pink, cheap, and bubbly. It

was called Crackling Rosé. Does anyone else remember Crackling Rosé?

The problem with Paradise

is always the people who go there.

Johnson Lake declined rapidly as a fishing spot, and by the mid-70s,

it was only good for a few trout of the pan-sized variety. By and

by, the parks people stopped stocking it.

By the 1980s I had given up

on Johnson Lake. It was overfished, and the only catchable trout

at this time seemed to be spawners. And then an incredible thing

happened.

I was driving by one evening

for a nostalgic look at the lake of my youth. At most I'd hoped

to get a glimpse of an osprey or a rising trout. I parked my car

in a newly constructed parking lot with signs and fancy latrines

and picnic benches. I took our old path to the rise overlooking

the lake. I looked at the lake.

More accurately, I looked for the lake. In the evening light, it appeared to be gone.

Perhaps I blinked or shook my head. It was gone. The dam

at the near end of the lake had burst, leaving behind an ugly grey

scar. A prank, I was told later. I raced down to what had been the

shore of the lake. I leapt into the muddy cavity. I walked all the

way down to the middle of the lake to what would have been one of

the deepest holes. All I could find was a trickle from the feeder

stream.

How many magnificent memories

had that lake held? Standing in the muddy bottom, I had a last look

and slowly trudged back. Perhaps a hundred feet from shore my foot

dislodged something that made me look down. A wine bottle. It was

unbroken and it had no label. But I could tell at a glance from

the shape and colour that it had once been a bottle of Crackling

Rosé. I suppose it could have been the bottle of some

other folksinger, equally drunk and irresponsible, but I think it

was mine. I took the bottle, communed with it for a while, and threw

it into the garbage container next to my car. But the bottle wouldn't

go away. It contained messages from those carefree years. 1960,

1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965 ...Michael row your boat ashore,

Hallelujah...

This story began with the

discovery of my wine bottle. The lake of all memories seemed to

disgorge a sad and bounteous flow of them. I had heard often enough

that the mind is like a lake that harbours memories in the great

Unconscious. But now it seemed to me that the lake was like a huge

mind. The more I looked at its vast muddy grey container, the more

it poured out the ghosts of its former life, and mine. I was saddened

by the usual things. The loss of youth. The loss of that feeling

that said the sky was the limit. The inevitable comparisons between

the bounteous past and the fishless present. But I think what bothered

me most of all was that I had betrayed my lake. I'd made it known

to mobs of people unworthy of its great gifts. I'd conspired against

my lake by leaving my trash behind and using it merely for my pleasure.

I had not taken the time to become my lake's custodian.

Stories like this are legion,

and they almost always end in a sad nostalgic sigh. But this one

doesn't. A few weeks ago I was in Banff on business. The town had

transformed from a place where families came to stay and see the

wonders of nature to a place where wealthy foreigners come to shop.

Walking down Banff Avenue was an agony. I decided to get out of

town and go for a drive. It was more habit than intention that took

me out to Johnson Lake, and there I made another amazing

discovery: it was once again brim full of water and trout! If there's

a god that presides over this earthly Paradise, he works for the

fisheries department and stocks fish for a living. He is the Johnny

Appleseed of the freshwater kingdom. God bless him wherever he goes.

If you should happen to come

upon my new old lake, you'll have no problem recognizing me. I'm

the bald guy in the belly boat who floats like a frog and hums old

folk songs. I'll watch how you dispose of your garbage, if you stick

to your limit, whether you bring a ghetto blaster to drown out the

sounds of the wilderness, whether you tear up the trail with your

ATV. If you fail any of my tests, I will be unforgiving. If you're

foolish enough to throw a bottle into the lake, beware. You may

not see me do anything, but if a huge bear should amble

down to your campsite and send you up a tree, don't say I didn't

warn you.